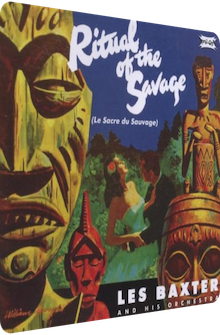

Les Baxter

Ritual Of The Savage

1951

Ritual Of The Savage by Les Baxter (1922 – 1996) could — and ostensibly should — have been one of the earliest, initial reviews on AmbientExotica, as it is considered one of the two undeniably essential benchmarks of the Exotica genre, the other being Martin Denny‘s eponymous work from 1958. Instead, I saved this moment for the Big 500. I am not a numbers guy per se, nor are personal achievements and trophies anything to cherish in a non-platform, website-related context, so without further ado or vanitas, let me dive right into Ritual Of The Savage.

Recorded in May 1951 and subsequently released on Columbia Records before there even was such a genre thing as Exotica, Ritual Of The Savage is hailed as the genre‘s first proper album beyond the proto-exotic touches in the veins of Les Paul and Mary Ford‘s twangy Brazil (1948), and way beyond the occasional cinematic score of pirate flicks or jungle pictures. If symphonic music is the listener‘s forte, then Baxter‘s later works more or less approach the concept in a reduced, more intimate manner (African Blue from 1969 comes to mind). Ritual Of The Savage, however, offers both the colorful traits, sumptuous strings and wide panoramas as well as contextually sophisticated drums Baxter is known for. This is not simple Easy Listening shovel ware, but the real deal. This remark is all the more astonishing, considering that the Exotica genre had yet to be established. Not unsurprisingly, then, does this album contain the platinum standard Quiet Village, penned by Baxter himself; it is the most covered hymn of the genre encompassing hundreds of different treatments, from unplugged harmonica solo sessions over mariachi versions to pompous Far Eastern gong arrangements.

To say it up front: Ritual Of The Savage is not my favorite Les Baxter record, but its stylistic features and artistic awareness are hard to ignore. For instance, all of its twelve compositions are specifically written by Les Baxter; a lot of them reappear to this day in various shapes and forms on albums by different artists, so it is not just Quiet Village in the limelight, but a whole lot of back-then-soon-to-be classics bathing near that spotlight too. While the album offers a vivacious journey from start to finish, with some of the greatest percussion and drum injections on any symphonic Easy Listening record, Ritual Of The Savage is also a mixed bag. Not quality-wise, but in terms of the overarching concept, i.e. the aural and continuous visualization of the intended subject at hand. Baxter‘s most fleshed out concept album — if you allow me to use this terms far away from Progressive Rock circles — is Jewels Of The Sea (1961), in my humble opinion. But another thing is also true: a well-versed, varied Exotica record might beat a conceptually more stringent counterpart any time, provided that it isn‘t too erratic.

And indeed, Baxter is having none of that. Although it turns out that Ritual Of The Savage is not as ritualistic or as prone to savage behavior as imaginable, it is a treasure trove to behold. And it does evolve after all: while the first few compositions are enclosed in a more rational setting audio-wise despite their adventurous titles, Baxter crosses that quasi-commonplace threshold very soon and delves into the exotic and melodious. Real or perceived danger is far away, the drums are playfully intimidating while lilac strings wash over the listening subject. The twelve tracks are being looked at in greater detail over the course of this review.

Busy Port, the first composition, is rooted both in the classical Easy Listening world and simultaneously functions as the first marker of Baxter‘s exotic outing. The flutes are whirling, the marimba‘s teal-colored timbre drops through the piano specks. Without overanalyzing (here? On AmbientExotica?) the connection between title and arrangement, let me jot down the thought of the listening or traveling subject still being situated in Occidental lands and surroundings here. Less mysterious, more jolly and based on the solid foundation of trumpets and trombones, this is the most normal and common composition on this album, at least in the very arrangement as presented by Les Baxter. Further exotification took place at later points thanks to the usual suspects Martin Denny and Arthur Lyman, but here this original lacks the paradisiac notion… while thankfully exuding and even eclipsing the middle class wanderlust of the 50‘s.

In an Easy Listening context, the follow up Sophisticated Savage’s sophistication is a no-no, but it comes close enough to being versatile, though it is not necessarily placed in a well-versed spectrum. Playful yet unexpectedly dark due to the ham-fisted dulcimer/harpsichord nucleus coated in maraca blots, this composition seamlessly connects to Busy Port in that the exotic is getting normalized and the faux-baroque West getting augmented by the unknown. More of a clash than a well-oiled machinery, Baxter‘s arrangement proves — maybe unintendedly — that this is uneasy Easy Listening; quite the achievement in the year of its release.

Up next is Jungle River Boat: This is the first of three dedicated jungle-themed outings, probably the glitziest production on the album, and it makes for a great alternative soundtrack to adventure movies in the vein of African Queen from 1951 starring Katherine Hepburn and Humphrey Bogart. The uplifting song pushes ever-forward. The woodwinds and soft marimbas provide the teal-colored silkened jungle backdrop to the whirling flutes and iridescent drums. Watch out for the powdered harpsichord intermezzo, a curious but welcome central European motif within the choir-induced exotic epicenter.

Jungle Flower, then, showcases that you can have quite the mellow life in the underbrushes. The title gives this welcome drowsy state away: Baxter musically zooms in on the floralcy. Two thirds of Jungle Flower provide an aureate piano aorta hued in sanguine string washes and cautious maraca-based glitters. The final third colorfully zooms out into the fields and meadows, what with its flashing congas, two shifts in rhythm and tempo, drumming away the moony atmosphere in favor of an upbeat revolting dance. Exotica as a genre can be many things — this very tune encompasses several of its styles in a span of less than three minutes, in an album that invents the genre.

Barquita, meanwhile, is shortest track; less than two minutes long, this interlude enchants with its airy polyphony of alto flutes and the aqueous glissando of harp helixes in-between the various clanging shakers and drums. The percussion is noteworthy in that it contains an echo, but a delightful one, making Barquita an immersive, fully fledged tune leaving room for reverb and lacunar grids. This boosts the plasticity even more, and as side A of Baxter‘s first Exotica album progresses, so does the notion of languor and drowsiness. The audacious polysemy wanes and makes room for lush greens and plastic jungles.

The final composition of side A is the mighty Stone God, and this one is figuratively for the heart. It is decidedly fast-paced throughout its runtime and consecutively shifts its rhythm. The aforementioned reverb of the percussive devices is the argentine yin to the fiery flutes‘ yang. Cheeky and constantly winking, Stone God exchanges a potential shock-and-awe melodrama for a wispier tunnel vision. While not being smoking fast per se, this tune leaves an important mark on the album, showing that a wound up tempo is a good trick to rev up the excitement.

Side B launches with the Exotica genre‘s platinum standard called Quiet Village. Reinterpreted and disassembled by hundreds of conductors and Jazz combos, there must be a reason why it is this very tune out of many that left the ever-important mark. There is one obvious answer that bears repeating: the melody itself is memorable enough in any context, only to be outshone by Baxter‘s arrangement. The strings sound enormously lush and full, their magenta-colored omnipresence watching over the sun-kissed piano section. The piano is particularly soft, less honky tonk-like, more wadded and silken, not to mention the great maraca coppice; these maracas are used in such a way their sustain coats the interstitial silence, appearing more wave-like, gouache-inspired than polka-dotted. Quiet Village is the most-cited Exotica piece ever, and thanks to Baxter‘s original, it was never a stigma in the first place but the very hallmark to begin with.

Jungle Jalopy could be called the corkscrew tune; fortunately, all vertigo-based side effects are left out of the composition. A serpentine affair to begin with, the four-note theme never disappears completely, turning from a flute-based magic wand-like apparition over a saffron-hued oud installment to a more playful woodwind outing, finally interchanging between these states. While everything is perfectly exotic and easy to listen to, Jungle Jalopy is the only track on Ritual Of The Savage that lets healthy bits of uncertainty, paranoia and caution into paradise. The pointillistic woodwinds soften this impression, but do not be mistaken: the mentioned four-note motif is haunting you for better or worse.

Every good adventure-filled ritual as viewed through Hollywood‘s lens needs a coronation, and so Baxter‘s Coronation features the most flaring brass sections of the whole album. Towering fanfares pierce through the majestic air, and if that does not do the trick for one listener or the other, the setup eventually makes room for an exquisite all-percussion sequence that hammers the idea of a benevolent festival home. Coronation is but one example where a large orchestra can rightfully shine by broadening the horizon and overcoming all limits with the power of lots of instruments. Sometimes, less is more… but, oh boy, not here.

Love Dance meanwhile is almost the reprise to Coronation, sharing many a — probably accidental — tone sequence with its bigger brother while venturing into the benign twilight, making use of softer timbres and pastel hues. The drums are fuzzier and tame for the most part, and for the first time, a silent darkness — or dark silence — is allowed to reign. Decidedly midtempo, Love Dance is ostensibly the least impressive of Baxter‘s offerings, but what it lacks in oomph and pizzazz it gains in completeness and stringency.

The penultimate Kinkajou follows and lets the blazing colors back into the album‘s intrinsic world. Inspired by Latin classics such as The Peanut Vendor, the frilly flute fusillade that greets the listener at the beginning makes room in the second half for another drum-infested, tempo-shifted aftermath that provides a different tonality overall. Both parts could not be more different, and while you could have one without the other, they make Kinkajou what it ultimately is: an ambiguous alteration of Mexican folklore and Polynesian puissance; viewed through the aforementioned Hollywood lens, naturally.

While Kinkajou shifts its shape during its runtime, the grand finale The Ritual actually shifts the shape of the whole album, feeling peculiarly de trop and magnificently right at the same time. Maybe for once, Les Baxter concocts a tune that completely adheres to the album‘s title, cover artwork and idea. One striking addition makes The Ritual a standout track, and again for better or worse: indigenous male chants. Without even a trace of Baxter‘s phenomenal melodies, the outro is filled to the brim with drums, varying rhythms and energetic performances by the chanters. This is a wonderful addition to the album‘s roster of 12 tracks, for it encapsulates the per-track dichotomy like no other composition, while at the same time being the pitch-perfect example for a successful unison between style and form, promised theme and executed art form.

To give a final thought or two: Ritual Of The Savage remains the ever-important benchmark when it comes to orchestral Exotica music. The melodies are so predominant, lush and luxurious that they transform delightfully well into other genres. After all, Baxter‘s originals appeared — and still appear — time and again in albums, EPs and samplers produced by Exotica combos. It is thus a matter of taste which arrangement is preferred by the respective listener: the sumptuous string-infused one or the more intimate but occasionally energy-boosted dedication of a quartet or quintet.

One thing is for sure: since orchestras have always been a costly affair and have therefore waned from the public presence from the 70‘s onwards (Disco was the last genre that was frequently backed by non-sampled flashy big bands and suave conductors), Les Baxter‘s arrangements are becoming increasingly valuable from various points of view, be they “simply“ aesthetic, production-based, high fidelity-driven or grounded in music history. Ritual Of The Savage is true-to-form Exotica despite quasi-launching the genre, but it is especially mind-blowing as a “mere“ work of Easy Listening. True, the exotic and the West mesh, all the while the instruments and arrangements often clash and feel de trop, but this only emboldens the fantastical.

Listeners are in for a treat regardless, and while I prefer Baxter‘s subsequent works which contain a golden thread arrangement-wise in lieu of merely title-wise, I cannot dismiss the importance of Ritual Of The Savage — despite this being the 500th Exotica review. Some things take time, purposefully so, as I couldn‘t dedicate this humble milestone to a better suited Exotica LP.

Exotica Review 500: Les Baxter – Ritual Of The Savage (1951). Originally published on Oct. 19, 2018 at AmbientExotica.com.